Using Art to Demystify Science

Research & Inquiry

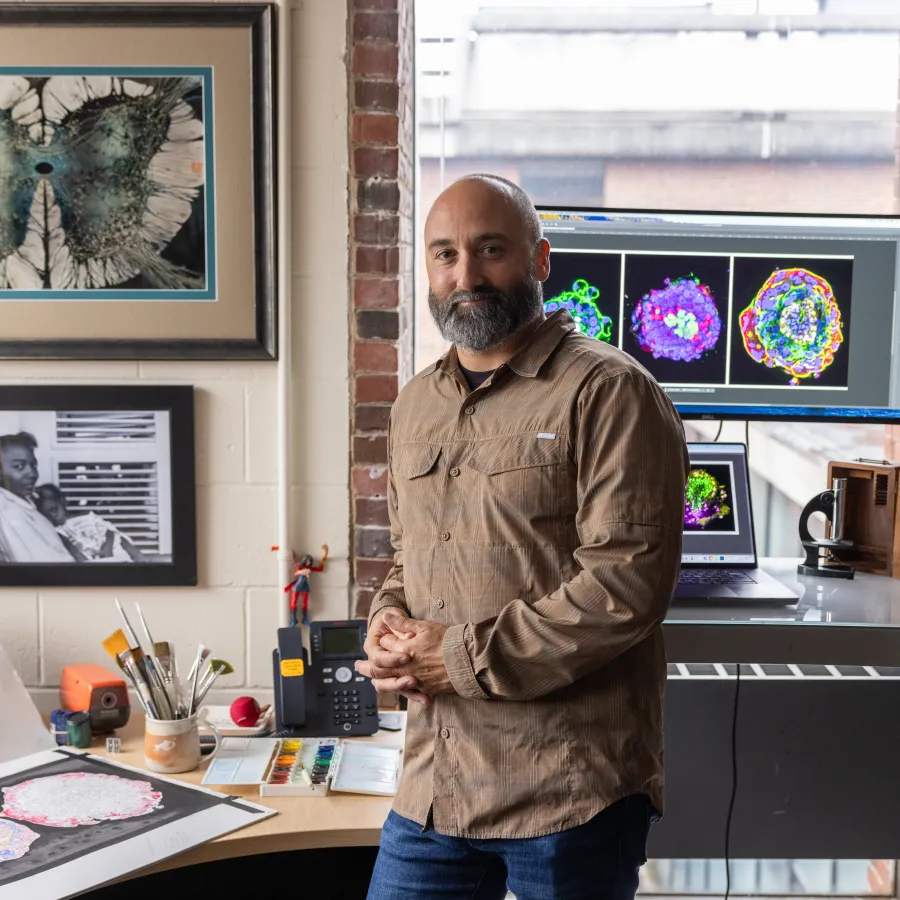

Professor Michael Barresi is creating a traveling art exhibit about how human life develops

Photo by Jessica Scranton

Published November 3, 2025

When does life begin?

Professor Michael Barresi has long been exploring that question in his research in development biology. Now, he’s taking up the topic in a new way: via visual art.

Barresi, who is professor of biological sciences and chair of the Smith College neuroscience program, is creating artworks from images of human embryos for a traveling exhibit he plans to take to colleges, conferences, museums, and other public venues.

In addition to capturing the visual beauty of cell biology, he hopes his paintings, mosaics and sculptures will foster deeper understanding of scientific data, including how data interpretation degrades the farther it moves from the original source. The underlying goal is to support more informed debate about the complexities of human development.

Why art?

“All my life I’ve been an amateur artist,” says Barresi, who minored in studio art in college and, at one point, considered becoming a scientific illustrator. “I’ve also been reflecting on how the public responds to scientific data, and how scientists can help people be more engaged in topics like when life begins.”

That particular topic can be controversial, Barresi notes, as it touches on religious and political beliefs, as well as deeply personal experiences.

Using art as an entry point can help make the science of human embryology more accessible. “Art is a magnet for engagement and curiosity,” Barresi says. “Art invites people in and puts them in a more open mindset.”

Professor Michael Barresi works on watercolor paintings of human embryo cells.

Photo by Jessica Scranton

Visitors to the planned exhibit will answer brief survey questions about the artworks they see, to help emphasize that scientific data can be interpreted in different ways.

Barresi hopes the exhibit will spark deeper awareness of the complexities of determining when life begins. For instance, he notes, few people may realize that the anatomy of the human heart is not complete until birth, when a baby’s first breath closes a flap and divides the two atria.

His new outreach project, which is supported by a National Science Foundation grant, “is an opportunity to do something different with data,” Barresi says.

“Fortunately, my field lends itself to the visual arts,” he adds, with a smile.

Barresi’s office in Sabin-Reed Hall is a testament to that idea, filled as it is with paintings, posters, and sculptures. On an elevated stand, a computer screen displays photographs of human embryo cells in vivid hues. At a nearby desk, Barresi has begun work on a watercolor painting of those same images. Next will come an oil pastel, a ceramic mosaic and, finally, a metal sculpture.

By comparing the artworks to photographs of embryos at different stages, visitors to the exhibit will be encouraged to reflect on “how they interact with and interpret scientific information and how much information is lost the farther you get from the original source,” Barresi says.

If the traveling art project goes well, he hopes to partner with fellow scientist-artists in communicating about other complex issues such as neurodiversity, evolution, and climate change.

”When we think about policy on these issues, do we truly understand the science?” Barresi asks. “Science communication is more important now than ever.”